“Annapolis may still be called ‘the finished city,’ and those who love her quaint old streets, her well-shaded gardens and her dark red walls of brick, can see in them something which no other city in this land affords.”

– Henry Randall (1869-1905), Architect, Annapolis Native

Annapolis enjoyed what’s been called its “golden age” from the late 1750s to 1776. At the time, the town was described by Jonathan Boucher, rector of St. Anne’s Church in 1772, as the “genteelest town in North America.” Annapolis served both as the county seat and Maryland’s capital throughout this period. During legislative sessions, its streets, inns, and houses were filled with prosperous plantation owners, merchants, politicians, sailors, craftsmen, and free African Americans. In contrast, servants worked off their indenture, or terms of service, and the enslaved population toiled to support a tobacco-based economy. Today, walking the brick streets of the Historic District that is downtown Annapolis, the voices of this diverse and multilayered heritage can still be heard while exploring the original buildings of the “golden age.” The social lives of the period’s Annapolis elite have long faded into history, but the architectural grandeur of the time still survives for us to enjoy.

-

-

Golden Age 1

The Town Plan

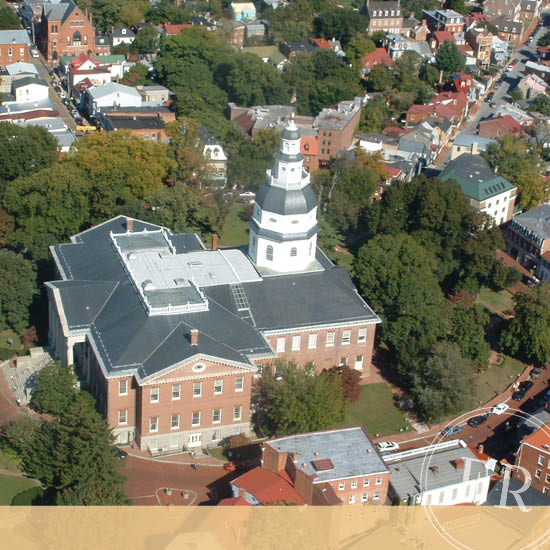

Governor Francis Nicholson, who moved the colony’s capital from St. Mary’s City to a small settlement on the Severn River in 1695, had the most profound effect on the layout of the new town. Apparently inspired by European urban design, he created a new town plan in 1696, whose central concepts of circles and squares with irregular intersections gave, as artist F.B. Mayer wrote nearly 200 years later, a “picturesque variety which relieved the eye of the endless and tiresome monotony of our American checker-board system.”

In accordance with the new town plan, Nicholson reserved the two most prominent hills for buildings that represented state and church, the two pillars of colonial society: the Maryland State House (where George Washington resigned as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army in 1783 and where Congress ratified the Treaty of Paris, ending the Revolutionary War, in 1784) and St. Anne’s Church. Streets radiating from the circles provided impressive vistas from both sites. In 1779, the state’s General Assembly first met in the new, third State House built on the Public Circle; it is the country’s oldest state house in continuous legislative use.

-

-

Golden Age 3 1

Architecture and Craftsmen

The town flourished, so that by the close of the “golden age” more than 450 buildings had been constructed. To this day, downtown Annapolis is home to a greater density of original 18th-century buildings than any other U.S. city, making it a wonder of colonial architecture. The Judge John Brice House, begun around 1739, reminds visitors of the days before Annapolis’ building boom; his son’s far more elegant dwelling, the James Brice House (started in 1767), epitomizes the pinnacle of the “golden age.” William Buckland, a British-born joiner and builder, came to America to work on George Mason’s residence, Gunston Hall, in Virginia. Around 1772, planter Edward Lloyd hired Buckland to work in Annapolis on what’s known today as the Chase-Lloyd House (22 Maryland Ave). Two years later, the young planter Matthias Hammond hired Buckland to design the Hammond-Harwood House (19 Maryland Ave), considered one of America’s finest examples of a Georgian residence. Each of Maryland’s four signers of the Declaration of Independence is associated with one of the city’s elegant Georgian mansions: Samuel Chase as the original owner of the house Lloyd and Buckland finished, Charles Carroll of Carrollton (the Charles Carroll House, 107 Duke of Gloucester St.), William Paca (the William Paca House and Gardens, 186 Prince George St.), and Thomas Stone (the Peggy Stewart House, 207 Hanover St.). Three of the four houses are open to the public. These residences and many other examples of Annapolis’ “golden age” still stand today to illustrate the craftsmanship and architectural brilliance of the time.

-

-

Golden Age 4 1

Social Life

Annapolis’ fall and winter social season, when the Assembly was in session, saw Maryland’s leading planters and politicians return to their town houses. How did they amuse themselves? They generally followed British traditions, engaging in horse races, social and literary clubs, theater, dancing, and music. Impromptu races were first held wherever gentlemen gathered. By 1743, after the importation of Thoroughbreds into the colony, a formal race course was located just outside the city gates at Cathedral and West Streets and the Maryland Jockey Club presented its first silver trophy. In contrast to the raucousness found at the races, refined young ladies and gentlemen, educated in the fine arts of music and dancing, gathered in the Assembly Rooms on Duke of Gloucester Street (today the site of City Hall). Traveling theatre companies, such as the Company of Comedians, entertained the likes of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin among other notable figures.

Experience the Area

With the support of our local partners and associations, Chesapeake Crossroads is dedicated to preserving the attractions, locations, and stories that portray Annapolis’ “golden age.” If you are interested in experiencing the area’s rich history for yourself, you can plan a visit to one of our partner sites, look into a local tour, attend a local seminar or lecture series, or join us for one of many monthly events in the region.

If you’re looking for a peek into Annapolis’ “golden age,” there’s no shortage of its history in Anne Arundel County and the Chesapeake Crossroads Heritage Area. Click here to discover Annapolis’ “golden age” attractions that are open to the public.